2006, VANCOUVER, CANADA

WHERE I LIVED AND WHAT I LIVED FOR

EXHIBITED AT CONTEMPORARY ART GALLERY

CURATED BY JENIFER PAPARARO

The Ghost Whisperer: Myfanwy's Time in the Woods

by Peter Culley

“I live in the angle of a leaden wall, into whose composition was poured a little alloy of bell-metal. Often, in the repose of my mid-day, there reaches my ears a confused tintinnabulum from without. It is the noise of my contemporaries.”

—Henry David Thoreau

For an artist as acutely conscious of (and thus, perhaps, more acutely subject to) the tropes of popular culture as Myfanwy MacLeod, her three month Glenfiddich-sponsored residency in the semi-wilds near Dufftown north of Aberdeen in Scotland was a ready-made scenario, impossible to avoid—an artist “in the midst of life’s journey,” seeking Thoreauvian “simplicity” beyond the brutal machinations and stratifications of her home turf, moves into a landscape which turns out to be populated with ghosts. Less a Stephen King novel than a movie of the week circa 1973, with Suzanne Pleshette or Shirley Jones pecking out a novel in pastel wine country while Satanists (Ernest Borgnine, Mildred Natwick) gather in nearby barns.

The first of these ghosts is, of course, the one both tourist and hermit seek to escape, the immovable self with its crochets and endless, muttered, banal narrativizing, represented photographically in MacLeod’s installation both as a sheet-covered Halloween ghost self-portrait and a pair of floating grey eyes, warily peering through a mail slot. Abjectly standing on a plinth in a gallery the last-minute Halloween ghost reflects perhaps an understandable impatience with the dual personae of funny girl and second generation Vancouver conceptualist which, even if true, would certainly benefit from having a veil drawn over them for a few months, with the possibility of new selves road-tested against the artificial but blankish backdrop of a “residency.” But the mail-slot eyes peek both into an abode of fear and slightly to the right of a gallery audience, which may or may not be willing to tolerate such metamorphoses, however temporary.

To MacLeod, the realm of the dead and the art world are alike: filled with hungry spirits, offstage whispers, and clammy, invisible hands.

For the first week, whenever I looked out on the pond it impressed me like a tarn high up on the side of a mountain, its bottom far above the surface of other lakes, and, as the sun arose, I saw it throwing off its nightly clothing of mist, and here and there, by degrees, its soft ripples or its smooth reflecting surface was revealed, while the mists, like ghosts, were stealthily withdrawing in every direction into the woods, as at the breaking up of some nocturnal conventicle.

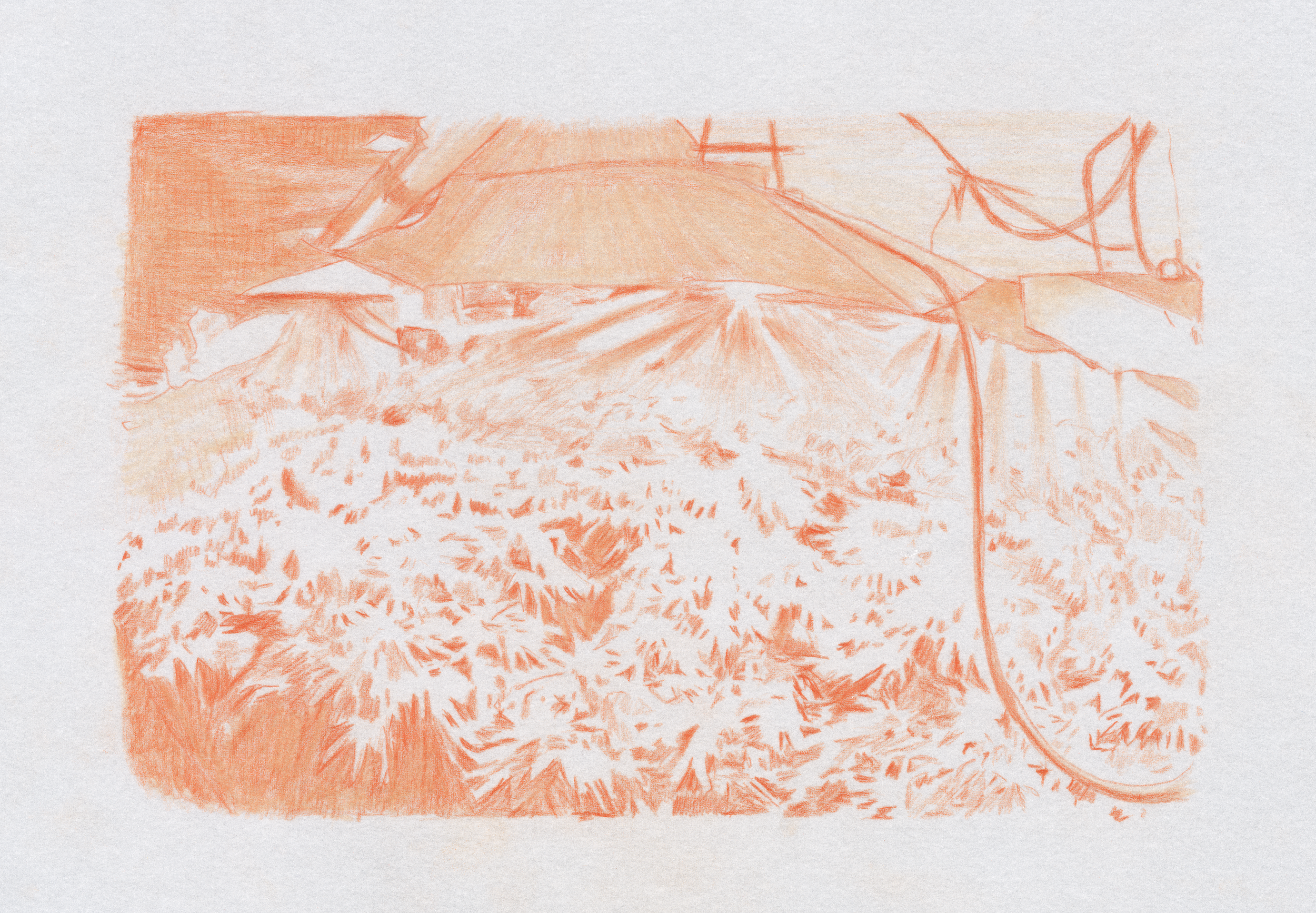

The Scottish landscape, too, is full of ghosts, and not only the bogies and sheela-na-gig ’s of legend; the dirty little secret of the single malt-and-shortbread imbibing, kilt-wearing “Highlands” is that it is the invention of a triumphant nineteenth-century Lowland/English aristocracy, the by-product of the displacement of millions to make way for sheep. In order for the “landscape” to be produced, its actual inhabitants had to be removed. The process was so comparatively sudden and complete—the processes of recovery so slow—that great tracts of northern Scotland still bear visible scars. The treeless moors dotted with picturesquely abandoned buildings are (like most landscapes—just look out your window) the visible record of a series of financial calculations as pitilessly detailed as a ledger book. But Macleod’s evocations of “nameless” dread in the images of a ruined cottage close to where she was staying—ominous corners, half-open doors, an overall sense of premature and hasty abandonment—seem generated by psychological drift, by dread itself, as much as any urge to point out the destructiveness of capitalism’s “hidden hand.” And although the meticulous orange drawings—derived from a “public service” website—of BC marijuana “grow-ops” in the next room depict an economy as radically transformed as was the Highlands (only its prized high-end consumer intoxicant is “BC Bud” instead of single-malt), it is significant that the guttings of bourgeois space they depict have left their exteriors carefully untouched. It is as if the ruins of the New World are chiefly hidden, interior, the suburban dream outwardly all smiles, bright siding covering inner rot. Just visible beneath MacLeod’s stylization is the original images’ drug war invitation to regard the faulty wiring, bent pipes, and mould with a mixture of horror and forensic glee, the better to turn in our neighbours before land values sink.

On the gallery wall opposite the drawings there even seems to be some mould growing, in unwholesome rusty flakes, as if, spore-like, crime could spread from anonymous basements into the spaces of art by the power of association. In MacLeod’s anti-pastoral the contagion is universal, an itch just under the skin. Grow-ops, Scottish ghosts, and cast-off personae can be suppressed but never eradicated. Abandoning things in the country just doesn’t work. Like pets, objects find their way back, and they’re different.

“Neither men nor toadstools grow so.”

—Henry David Thoreau

Right angle to the grow-op drawings a large round tinted mirror cuts off the “ghost” viewer’s escape and makes (with the rug) a kind of interrupted domestic space, a crime scene mounted on an imaginary plinth. The “mould” dares you to pick at it. The viewer is invited to regard the scene with a television coroner’s workmanlike indifference to horror. But in the opposite corner is the room’s dominating feature: a hank of hair wedged in an angle, as if being pulled through, a clear allusion to the horrifying final moments of the 1999 film The Blair Witch Project. I had already thought of the film a little earlier, looking at one of the photographs in the other room, which was of an unidentified blob whose barbed, tooth-like features had brought to mind probably that film’s second most terrifying moment: the quickly glimpsed final “recombined” state of one of the film’s unfortunate protagonists. Both these moments happen in the film so quickly that the images don’t really have time to properly register and thus (like the subliminal frames hidden in The Exorcist) imprint themselves on the unconscious as hallucination—bad memory. It is a trick as old as shadow puppets, maybe, but a good one. By moving such moments from the realm of flickering, perceptual doubt into prosaically realized sculptural form the “fear factor” is all but removed, but a residue of dread adheres like mould or a threatening stain.

Let us not play at kittly-benders. There is a solid bottom everywhere. We read that the traveller asked the boy if the swamp before him had a hard bottom. The boy replied that it had. But presently the traveller’s horse sank in up to the girths, and he observed to the boy, “I thought you said that this bog had a hard bottom.” “So it has,” answered the latter, “but you have not got half way to it yet.

Like Paul Verhoeven’s Starship Troopers (1997) from the same era, Blair Witch attains classic cult status chiefly through its prophetic power. Just as Verhoeven’s film predicted—in rich detail—not only the “War on Terror” but the accompanying slide into fascism, Blair Witch extended its pro-forma anti-pastoralism to offer viewers a glimpse of what, in less than a decade, would become a general condition, in the woods or out of them: that of wandering around, lost or misdirected, in a state of nameless worked-up dread at something you can’t really identify, a victim not only of external forces but the very mechanisms—art, say—that might once have offered mitigation. The deep unease that MacLeod’s Where I Lived, and What I Lived For (2006), registers is a general one, its details oddly generic even at their most personal.

Thoreau’s heroic transcendentalism splits the difference with Stephen King. The icy detachment with which MacLeod returns the viewer—perhaps having come once again to the mirror—to their precise amount of pre-existing background anxiety feels like the opposite of prophecy, but is oddly bracing nonetheless. Bristling a little at its own obliqueness, Where I Lived, and What I Lived For, feels like a transition toward a more openly confrontational mode for its creator. That she possesses the latent power to shock the show leaves little doubt.